Image by Smithsonian Institution via Flickr

Native American women, like their Arab, Asian, black and Latina sisters, have also struggled in naming their own identities. Christopher Columbus’s geographic muddling typed the indigenous people of the Americas as “Indians” for centuries. Today Native American and Indian are used fairly interchangeably, but there is growing awareness as to the number and diversity of remaining tribes.

Many Latinas of indigenous heritage, from tribes that reigned from Central America up into modern-day Colorado, unlike activists in MEChA, do not identify as indigenous people or Native Americans because of the racism that plagues American societies. This is largely due to white supremacy and linguistic bigotry–Spanish-speaking indigenous people do not identify with English-speaking indigenous people and vice versa, but again, white, patriarchal society also has a stake in keeping minorities from unifying.

“Women who wish to share their similar experiences ought to be able to do so but [they should] do so within the context of being mindful that we are part of a larger body of people under siege and all of us are needed in the struggle.”[1]

Native American women were the first people to experience the violence, racism and sexism the English, Spanish, French, Dutch, and Germans brought with them from Europe. Very few women’s histories have been recorded from the time of European invasion and those stories that have been retold are suspicious in their details.

“Along with Pocahontas, Sacajawea is the best known of Native American women; the fact that both are remembered for the assistance that they rendered to white men is an aspect of national history that deserves more thoughtful attention than it has received.”[2]

These two Native American women have received the highest “honors” available in U.S. culture: Sacajawea was immortalized on a coin and Pocahontas got her own Disney movie.

“By implying that ‘noble’ Indians like Pocahontas recognized the superiority of non-Indian culture and consequently wanted Europeans to overrun their lands, it allowed whites to rationalize their illegal and immoral seizure of Indian lands.”[3] Indeed, the whitewashed storytelling about Native Americans nearly always places European culture in a superior role, and only when the “savages” recognize this are they “saved” and brought into Christianity.

The sheer number of people who were killed by violence and disease after the arrival of Europeans limits the available historical examples of Native American women but, anthologies of Native American women have recorded stories from tribes across the country about remarkable and heroic women.

Among them is Lozan, “the only Apache woman known to have devoted herself fully to the life of a warrior.”[4] Because she took on a traditionally masculine Apache role she disregarded the traditional feminine role she would have taken on if not for her prowess as a warrior.

Many Native American cultures were far more accepting of variation in gender roles than Europeans ever were. Most Native American cultures throughout North America recognized and often revered the possibility of gender variation. The modern term for those people who felt both masculine and feminine is two-spirit. A transgender person, or two-spirit, is one who is born with one sex but feels that her/his gender role should be closer to that of the other sex. Two-spirits and those who are born intersexed, were historically seen as special, intellectual beings in many Native American cultures because they embodied both masculine and feminine spirits. In essence they were more whole as a person than anyone who was solely male or solely female could be. Recognition of this cross-gender identification has been documented in over 155 tribes in North America.

It was not uncommon for a woman who dressed and acted like a man to engage in sexual relationships with other women and historically there was much more acceptance of fluidity within identity and orientation in Native American cultures. While Europeans often conflate gender roles and sexual orientation, many two-spirit people were celibate, and therefore would not fit into the modern “homosexual” box.

Today Native Americans who identify as two-spirit “face homophobia and sexism from [their] own people, racism from lesbians and gays, and racism, homophobia, and sexism from the dominant society, not to mention the classism many Native Americans have to deal with.”[5]

Many Native Americans who identify as either lesbian, bisexual, transgender, intersex, or two-spirit are active in combating homophobia in hetero-normative societies, including Native American societies, and in combating racism in predominantly white societies, including the LGBTQAI society.

Those Native American women who are now fighting for equality and an end to racism, sexism, homophobia, classism, and ableism have an amazing repertoire of heroines to look up to from the middle of the 17th century on. Unfortunately the oral traditions that would have carried stories of heroes and heroines from before the European invasion were lost to racism, disease, and death.

One of the first Native American women to make it into the European historical records was Cochacoeske, the village leader of the Pamunkey, who signed the Treaty of Middle Plantation of 1677. “Unlike most agreements between whites and Indians, it attempted to be fair to both sides…. During the negotiations, she insisted that the treaty identify her as the leader, not only of the Pamunkeys, but also of several neighboring tribes.” Cochacoeske “chose to use negotiation rather than weapons to realize her ambition.”[6]

Another historical sister Native American women can look to is Molly Brant. The sister of Joseph Brant, a Mohawk chief, she “was perhaps the most politically powerful Native American woman during the late eighteenth century.” Even if she had not been the sister of the chief, “In traditional Iroquois society, women enjoyed a good deal of economic and political power,”[7] and were the owners of the land and what it produced.

While women did not commonly perform the same tasks as men, the tasks they did perform were generally as valued as men’s–something very different from the way women’s work is valued in modern American society. The status of women in many Native American societies was such that “suffragists regularly cited their status as evidence that women and men could and should have balanced roles.”[8]

Native American women, like all women of color in the United States, have historically been forced to choose whether their primary fight is against racism or sexism. Possibly because women already had some political sway within their own communities and had rights that were denied most white women, many Native American women chose primarily to fight for their rights as Natives.

Susette La Flesche Tibbles, an affluent woman of mixed Ponca, Iowa, and French descent, fought for the rights of Native Americans as a reporter and interpreter during the case of Standing Bear v. General George Crook in 1877 when, for the first time, Native Americans “were legally recognized as human beings.”[9] This landmark ruling was a major step forward for Native Americans, but legal recognition as human beings did not necessarily result in more humane treatment by the U.S. government.

Susette La Flesche Tibbles, an affluent woman of mixed Ponca, Iowa, and French descent, fought for the rights of Native Americans as a reporter and interpreter during the case of Standing Bear v. General George Crook in 1877 when, for the first time, Native Americans “were legally recognized as human beings.”[9] This landmark ruling was a major step forward for Native Americans, but legal recognition as human beings did not necessarily result in more humane treatment by the U.S. government.

Since the European invasion Native Americans were pushed off their land and forced to sign treaties that reserved only a small piece of their homelands for them and still today Native American reservations have some of the highest crime and poverty rates in the country.

Ten years after Standing Bear the Dawes General Allotment Act was signed into law. In trying to compel Native Americans to assimilate to white culture it did irreparable damage to the tribal structure of Native American communities by allotting small parcels of land to individuals in each tribe and then distributing the “surplus” amongst white colonizers. Heads of household received 160 acres, other adults 80, and minors 40, but until an 1891 amendment to the act married women were ineligible to receive land. After the amendment all adults regardless of sex or marital status were treated equally but the size of the allotments was halved.[10]

“The allotment policy depleted the land base, ending hunting as a means of subsistence. According to Victorian ideals, the men were forced into the fields to take on what had traditionally been the woman’s role and the women were relegated to the domestic sphere. This Act imposed a patrilineal nuclear household onto many matrilineal Native societies. Native gender roles and relations quickly changed with this policy since communal living shaped the social order of Native communities. Women were no longer the caretakers of the land and they were no longer valued in the public political sphere. Even in the home, the Native woman was dependent on her husband. Before allotment, women divorced easily and had important political and social status, as they were usually the center of their kin network.”[11]

“By dividing reservation lands into privately-owned parcels, legislators hoped to complete the assimilation process by forcing the deterioration of the communal life-style of the Native societies and imposing Western-oriented values of strengthening the nuclear family and values of economic dependency strictly within this small household unit.”[12]

Until the Indian New Deal overturned the act in 1934, some 90,000 Native Americans were made landless and an estimated 90 million acres of treaty land was taken from tribes across the country.[13]

“By the late nineteenth century U.S. policies toward Indians had deeply impoverished most tribes, particularly those confined to reservations in the West.”[14]

During the period in which the Allotment Act was active many women were working for more fair and just treatment of Native Americans such as Gertrude Simmons Bonnin, a mixed Nakota Sioux and white activist who worked in the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), the government agency responsible for dealing with tribes in America.

Bonnin supported the Society of American Indians, an organization established by Oneida activist Minnie Kellogg in 1911 to support pan-Indianism, or the unification of Native Americans for the rights of all tribes. The pan-Indianism movement began strong steps towards organizing various Native American tribes in 1912 when the Four Mothers Society, made up of people from the Chickasaw, Cherokee, Creek, and Choctaw nations banded together to take political action against the policy of allotment. In the same year the Alaskan Native Brotherhood and Sisterhood was formed to protect tribes’ natural resources.

Meanwhile Bonnin continued to be active in working for Native American rights until her death in 1938. She worked with the General Federation of Women’s Clubs to form the Indian Welfare Committee in 1921 and with the help of the Indian Rights Association persuaded the government to begin what would be the Meriam Report. Even though all Native Americans were finally granted U.S. citizenship in 1924, because Bonnin still felt Native Americans were being severely discriminated against by the government, she formed the National Council of American Indians in 1926.[15]

The Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934, also known as the Indian New Deal and the Wheeler-Howard Act, restored some sovereignty to Native American nations by allowing tribes to create their own governments and have input into reservation schools.

Even after this Native American children were forced to live in boarding schools far from their families. “The government still operates a handful of off-reservation boarding schools,”[16] and some students who attend them now are grateful for the opportunity to be surrounded by other Native Americans and practice their cultures. The reality of today’s Native American boarding schools lies in sharp contrast to the program implemented in 1879 that was based on a prison education system.

When Army Captain Richard Pratt opened the first Native American boarding school, the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, he did so with this philosophy: “all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”[17]

When Army Captain Richard Pratt opened the first Native American boarding school, the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, he did so with this philosophy: “all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”[17]

Indeed many students were killed in the century in which Native Americans were forcibly removed from their parents, renamed, forbidden to speak their own languages, and imprisoned in off-reservation boarding schools. Hard manual labor and emotional, physical, and sexual abuse were rampant in these schools and rules and discipline were often inappropriate and dangerous.

The Problem of Indian Administration, commonly referred to as the Meriam Report, published in 1928 was a scathing review of the U.S. government’s handling and treatment of Native Americans in all aspects of life. One comment on the teaching methods utilized in the boarding schools stated:

“If there were any real knowledge of how human beings are developed through their behavior, we should not have in the Indian boarding schools the mass movements from dormitory to dining room, from dining room to classroom, from classroom back again, all completely controlled by external authority; we should hardly have children from the smallest to the largest of both sexes lined up in military formation; and we would certainly find a better way of handling boys and girls than to lock the door to the fire-escape of the girls’ dormitory.”

After the Meriam Report, in the 1930s, “educated Indians were determined to fight for the rights of Indian people…. Indian women, such as Gertrude Simmons Bonnin and Ruth Muskrat Bronson, rose to prominence in this movement, which became known as Pan-Indianism because it encouraged Indians of many different tribes to work together to solve their common problems.”[18]

Bronson, a Cherokee woman who worked for the BIA, wrote Indians Are People Too and “she cautioned non-Indians that romanticizing Indian people could be just as destructive as stereotyping them. In the 1940s she also became involved with the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI), a national tribal organization dedicated to defending Indian rights.” Formed in 1944, today the NCAI is one of the largest organizations working for the welfare of Native Americans in the UNited States. [19] She also worked to improve living conditions on Native American reservations through her creation of the women’s group Ee-Cho-Da-Nihi.

Another Native American woman who was actively fighting for civil rights during this time was Alice Mae Jemison, of mixed Cherokee and Seneca heritage. Because the BIA had “promoted several policies that were meant to ‘protect’ Indians but that had ultimately helped to make them the poorest minority group in the nation,” Jemison published a newspaper article in 1933 which demanded the government “Abolish this bureau with its un-American principles of slavery, greed and oppression and let a whole race of people, the first Americans, take their place beside all other people in this land of opportunity as free men and women.”[20] In 1935 Jemison also served as the official spokesperson for the American Indian Federation.

The latter half of the 20th century saw major participation by Native American women in fighting for justice. Betty Mae Tiger Jumper, of mixed white and Seminole heritage, made history in 1967 when she became the first elected female tribal chief of any Native American tribe.[22] Her success helped to pave the way for other Native women.

The American Indian Movement (AIM), “Largely composed of young urban Indians inspired by the African-American civil rights movement of the early 1960s… advocated a renewed respect for Indian traditions and sought to make the U.S. government live up to the treaty promises it had made to Indians throughout the country.”[23] Also known as the Indian Rights Movement and Red Power, AIM included many female activists who were integral to its key campaigns such as the occupation of Alcatraz Island, the Trail of Broken Treaties–a protest march at the nation’s capital, and the occupation of Wounded Knee, amongst other activities.

One young mixed Lakota Sioux and white activist, Mary Brave Bird, even gave birth at Wounded Knee as “a symbol of renewal, a tiny symbol, a tiny victory in our people’s struggle for survival.”[24]

Wilma Mankiller, a disabled, mixed white and Cherokee woman, was vital in organizing and fundraising for the occupation of Alcatraz by Native Americans. She would go on to be elected the first female chief of the Cherokee Nation from 1985-1995, despite concerns that “electing a female deputy would be an affront to God and would make the Cherokees a laughingstock among other Indian groups.”[25]

Other prominent Native American women active during the 1970s included Ramona Bennett, chairperson of the Puyallup Tribal Council whose “combative brand of activism during this turbulent period helped prevent the dissolution of her tribe,”[26] and Ada Deer who founded Determination of the Rights and Unity of Menominee Shareholders (DRUMS) and has thus far been the only woman to head the BIA as the Assistant Secretary-Indian Affairs, from 1993-1997.[27][28]

Choctaw activist Owanah Anderson was also an integral member of the fight for Native American women’s rights in the 1970s. She served in 1977 as a co-chairperson of the Texas delegation to the Houston Women’s Conference, and then joined the Committee on the Rights and Responsibilities of Women under the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. “From 1978 to 1981, she also served on the Advisory Committee on Women organized by President Jimmy Carter, [and she] founded the Ohoyo Research Center in 1979.”[29] In the past she also served as a project director for the National Women’s Development Program and on the board of directors of the Association for American Indian Affairs. While Anderson is well known throughout Native American communities for her activism, her Micmac contemporary, Anna Mae Aquash has achieved legendary status.

Aquash participated in the Trail of Broken Treaties and was married during the Native American occupation at Wounded Knee to showcase “her commitment to the fight for Indian rights.”[30] Aquash was an effective organizer and leader, drawing Native American women into the causes of AIM when its male leaders could/would not. Tragically, Aquash was murdered shortly after participating in Wounded Knee with AIM leadership claiming it was the work of the FBI and many Native American women claiming it was the work of the male leaders of AIM “who incorrectly believed she was a traitor.”[31]

Today the group Indigenous Women for Justice[32] fights for an answer in Anna Mae Aquash’s murder and follows the events of the trials of those men who have been accused with involvement in her murder nearly 35 years ago.

Native American women today are just as active in fighting for their rights as Native Americans and as women as they were 40 years ago. In 1970 white and Comanche activist LaDonna Harris created Americans for Indian Opportunity and has served as its president ever since. Her active involvement in environmental issues and feminism in conjunction with indigenous issues have made her a force to be reckoned with. She chaired the National Women’s Advisory Council of the War on Poverty in 1967; served as a representative of the Inter-American Indigenous Institute; was a presidential appointee to the U.S. Commission on the Observance of International Women’s Year,[33] the National Council on Indian Opportunity, the White House Fellows Commission, and the Commission on Mental Health; has served on dozens of national and advisory boards dealing with women’s and indigenous issues including NOW and the ACLU; and participated in the founding of the National Indian Housing Council, the Council of Energy Resource Tribes, the National Tribal Environmental Council, the National Indian Business Association, Common Cause, the National Urban Coalition, and the National Women’s Political Caucus.[34]

Another environmental activist, Winona LaDuke, an Ojibwe and Jewish woman, founded the White Earth Land Recovery Project,[35] the Indigenous Women’s Network, and Honor the Earth.[36] She was previously involved, as were many of the above-mentioned activists, with WARN– Women of All Red Nations, to prevent forced sterilization among Native American women.

Another environmental activist, Winona LaDuke, an Ojibwe and Jewish woman, founded the White Earth Land Recovery Project,[35] the Indigenous Women’s Network, and Honor the Earth.[36] She was previously involved, as were many of the above-mentioned activists, with WARN– Women of All Red Nations, to prevent forced sterilization among Native American women.

Other women like Paula Gunn Allen, a mixed Laguna Pueblo, Sioux, Lebanese and Scottish author, worked to increase tolerance for gays and lesbians within Native American communities. Gunn Allen did so with her work The Sacred Hoop: Recovering the Feminine in American Indian Traditions[37] while Chyrstos, a Menominee, Lithuanian and French two-spirit has done so with her work Not Vanishing and by contributing to This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color.

Another two-spirit activist, Ojibwe Carol LaFavor fights for Native Americans with HIV/AIDS and founded Positively Native to support the Native American community. Other organizations in which Native American women fight for their rights include the United Indians of All Tribes Foundation,[38] the American Indian Institute,[39] and the Native American Rights Fund.[40]

Native American have fought since their first interactions with white invaders for their rights and will continue to do so within whatever women’s/indigenous/women of color framework they choose. “Like women everywhere, indigenous women do not want others defining for them what it means to be a woman.”[41]

[1] Camper, Carol ed. 1994. Miscegenation Blues: Voices of Mixed Race Women. Sister Vision: Toronto, Canada.

[2] American Women’s History Doris Weatherford. 1994. Prentice Hall General Reference: New York.

[3] Sonneborn, Liz. A to Z of Native American Women. Facts on File, Inc.: New York. 1998.

[4] Sonneborn, Liz. A to Z of Native American Women. Facts on File, Inc.: New York. 1998.

[8] Mankiller, Wilma. 2004. every day is a good day: Reflections by Contemporary Indigenous Women. Fulcrum Publishing: Golden, Colorado.

[12] Gibson, Arrell M. “Indian Land Transfers.” Handbook of North American Indians: History of Indian-White Relations, Volume 4. Wilcomb E. Washburn & William C. Sturtevant, eds. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1988.

[13] Case DS, Voluck DA (2002). Alaska Natives and American Laws (2nd ed. ed.). Fairbanks, AK: University of Alaska Press.

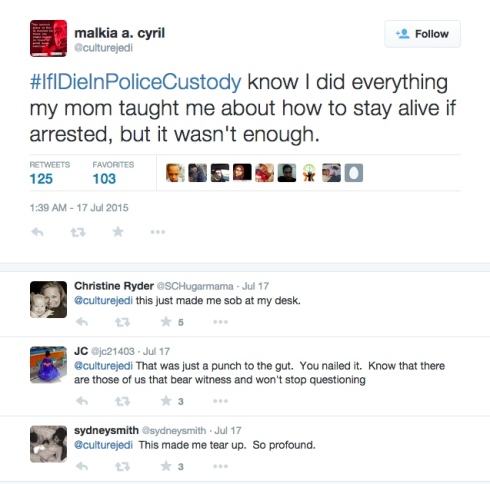

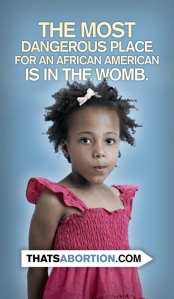

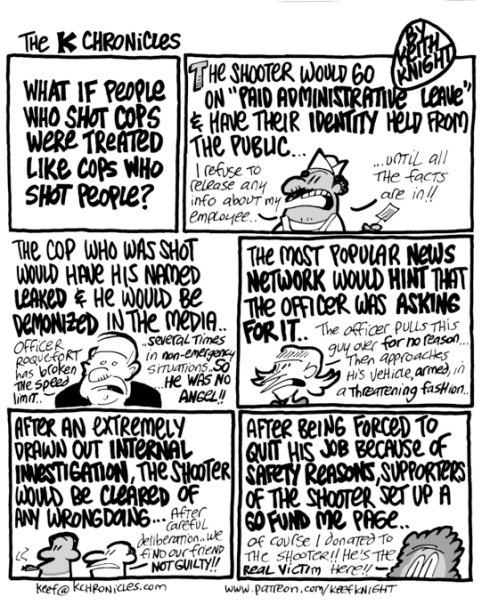

This piece explores how the justice system views Black women, here five Black women share their experiences with the police, read 60 more Black women’s stories here, listen to this spoken word piece about being a Black woman, here you can watch Black women speak out, and this is a good example of Black people’s realities. The disgusting truth of the matter is that any black person in America could have been Sandra Bland, and age, gender, disability, innocence or any combination of those don’t change that. The biggest lesson I’ve learned throughout the past year is that Black people rightly fear the police. Would more female police help???

This piece explores how the justice system views Black women, here five Black women share their experiences with the police, read 60 more Black women’s stories here, listen to this spoken word piece about being a Black woman, here you can watch Black women speak out, and this is a good example of Black people’s realities. The disgusting truth of the matter is that any black person in America could have been Sandra Bland, and age, gender, disability, innocence or any combination of those don’t change that. The biggest lesson I’ve learned throughout the past year is that Black people rightly fear the police. Would more female police help??? White folks–we NEED to talk about our privilege and how our appropriation of other cultures is not only damaging but violent. Here are just a few things you need to know before we move forward so please take a moment. You should also read this, this and this before going any further. Also, here’s what would happen if someone who doesn’t look like me got in a cop’s face, and here’s what kids will be learning about our country’s racist history in school. Speaking of school you should really check out these two truth bombs. And if you’re (somehow) still questioning why anti-racism efforts *must* be integrated into feminism read this. If you need more resources on learning about racism there are more than 30 there. Finally, here is what one woman of color wants white allies to know. What I need from you is to share these truths as far and wide as you can, #SayHerName and the names of all of the people killed by police violence, regardless of color.

White folks–we NEED to talk about our privilege and how our appropriation of other cultures is not only damaging but violent. Here are just a few things you need to know before we move forward so please take a moment. You should also read this, this and this before going any further. Also, here’s what would happen if someone who doesn’t look like me got in a cop’s face, and here’s what kids will be learning about our country’s racist history in school. Speaking of school you should really check out these two truth bombs. And if you’re (somehow) still questioning why anti-racism efforts *must* be integrated into feminism read this. If you need more resources on learning about racism there are more than 30 there. Finally, here is what one woman of color wants white allies to know. What I need from you is to share these truths as far and wide as you can, #SayHerName and the names of all of the people killed by police violence, regardless of color.

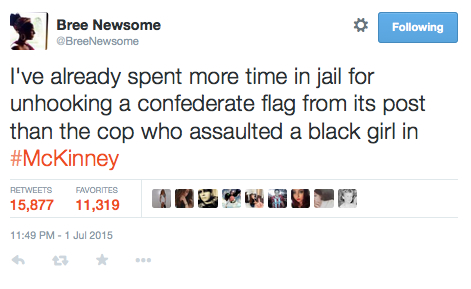

Last month we collectively mourned for the parishioners and families of the victims of the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church assassination, but the burnings of Black churches around the nation have been the backdrop against which the taking of Black lives by the police has been set. And while superheroes like Bree Newsome are shining examples of the courage to which we all ought to aspire, the confederate flag still flies regularly in the face of people of color whose existence is challenged everyday merely for the color of their skin. There aren’t enough ways to explain how wrong all of this is. In the safety of my white skin I am shocked and saddened and appalled by my fellow man. Reading about the destruction of Black lives and Black souls all day, everyday is exhausting, but the torment I’m experiencing from bearing witness to these atrocious human rights violations is a sliver, a fraction of what Black people living in fear of being killed by the police or by any of the myriad other racist institutions in our country are forced to deal with throughout their lives. Since it is impossible for me to share the gravity and weight of their reality with them, to take on a just portion of their load, the absolute least I can do is bear witness to these truths, do my part to hold police accountable, and demand change.

Last month we collectively mourned for the parishioners and families of the victims of the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church assassination, but the burnings of Black churches around the nation have been the backdrop against which the taking of Black lives by the police has been set. And while superheroes like Bree Newsome are shining examples of the courage to which we all ought to aspire, the confederate flag still flies regularly in the face of people of color whose existence is challenged everyday merely for the color of their skin. There aren’t enough ways to explain how wrong all of this is. In the safety of my white skin I am shocked and saddened and appalled by my fellow man. Reading about the destruction of Black lives and Black souls all day, everyday is exhausting, but the torment I’m experiencing from bearing witness to these atrocious human rights violations is a sliver, a fraction of what Black people living in fear of being killed by the police or by any of the myriad other racist institutions in our country are forced to deal with throughout their lives. Since it is impossible for me to share the gravity and weight of their reality with them, to take on a just portion of their load, the absolute least I can do is bear witness to these truths, do my part to hold police accountable, and demand change.